Consanguinity

Should inbreeding be considered harmful?

It is commonly believed that inbreeding is harmful. Marriage between close relatives is forbidden by most legal codes. This covers brother-sister and parent-child incestuous unions, which are almost always strictly prohibited, but it often extends to forbidding first-cousin marriages too. In the United States, first-cousin marriage is a criminal offense in nine states and subject to civil sanctions in a further 22 states. There are clear reasons for the prohibition.

Weighing the Genetic Risks

Humans reproduce sexually and are "diploid", carrying two copies of (almost) every gene, one from each parent. A mutation in one of these copies can occur without necessarily showing ill effects, in which case it is silently passed down from the carrier to about half the offspring on average. However getting two copies, one from each side of the family, can be harmful. Marrying a relative increases your chances of getting two copies of a mutant gene. For first cousins, the risk of developing a disorder is multiplied, but this depends on how common the mutant gene is in the breeding population that one is drawn from.

If a recessive gene is found in 10% of people, and your parents are unrelated, then the chance of getting the disorder is only 1%. However if your parents are first cousins, then the chance is higher, at 1.56%. Your risk is multiplied by 1.6. Counter-intuitively, the more rare the gene is in your gene pool, the larger that multiplier becomes. If the frequency is 5%, then offspring of first-cousins increase their risk from 0.25% to a 0.547% chance. That is 2.2 times the risk. If the recessive gene is ultra-rare, occurring in say 0.5% of the population, first cousin marriage increases the risk from 0.0025% to 0.00336%, which is 13.4 times the risk.

Notice though that these are pretty small numbers anyway. From the point of view of an individual, a risk of 0.00336% may seem to be practically zero. A moderately large number multiplied by an extremely very small number is still a very small number. But then one must weigh up the consequences of actually getting a disorder. If it is painful and leads to a very early death, even a small chance of getting it may be unacceptable, and one may choose to do everything possible to decrease the risk. Still, life is full of risks. Driving to the beach to buy an ice-cream and soak up some sun carries a non-negligible risk of a car accident or other misfortunes, yet many choose to take that risk as the price of living. Your cousin may be related to you, but perhaps she is also very pretty (a proxy for good health), exceptionally smart (you hope your children will be too) and wealthy (money is always welcome). Perhaps, too, if either party is unhappy they can get redress from relatives, who are not strangers. Plainly a large element of personal preference exists in the process of trading off risks.

This calculation is rather different at a societal level. Repeated inbreeding builds up consequences over time, becoming a burden. Indeed almost all sexually reproducing animals avoid close incest purely by instinct. The aversion that humans feel to incest is certainly instinctual. It could not have evolved otherwise, since each individual does not have enough time or experience to work out the long-term consequences of close inbreeding.

Historical Examples of Inbreeding

Given that this is so, it may be surprising to learn that some degree of inbreeding has been widely practiced in human history, and is still practiced today. Influential dynasties have tended to inbreed to a certain extent over prolonged periods. A famous case is the Rothschild family of banking magnates. Over two centuries, the 18th and 19th, about a third of all marriages involving that family were between first cousins. As their progeny have shown, there do not seem to have been marked ill effects. Or, if there were, they were compensated for by other virtues, such as keeping wealth intact, leveraging trust, and acquiring many other favorable genes. Similarly the hereditary “rebbes” of the Lubavicher Hasidim, a sect of Orthodox Jews from Belarus, married mostly cousins since the 18th century and prospered up until the present day.

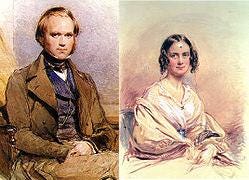

Many other examples could be given, not the least of which is the Darwin family. Charles Darwin married his first cousin Emma Wedgwood and produced very distinguished children, the males of which became first-rate scientists in their own right. Their relatives the Galtons were from Quaker stock, a nonconforming sect that became isolated within English society for centuries and became markedly inbred. Their most famous product, the scientist Sir Francis Galton, has a family tree that resembles a fishing net in places, as multiple lines cross over. Yet the family prospered in gun manufacturing and banking, a more traditional Quaker occupation (Barclays and Lloyds will be familiar names to many), and Francis is recognized as a genius. Grieg and Rachmaninov both married first cousins, as did Albert Einstein, Edgar Alan Poe, H. G. Wells, Mario Vargas Llosa and Friedrich Hayek. Thackeray, John Ruskin, and Lewis Carroll were products of cousin marriages and many popular Victorian novelists like Dickens and Trollope made it a theme of their fiction.

On the other hand, many other examples can be given where inbreeding has had harmful effects, in the sense of heightened rates of genetic disease and peculiar disorders. Ashkenazi Jews are relatively inbred and have much higher rates of Tay Sachs disease and certain other genetic disorders than other populations do. The Amish, Hutterites and Mennonites in America are also relatively inbred, and have elevated rates of certain genetic conditions. A lot depends here on how long a group has been practicing inbreeding and other variables. Often the presence of a founder or set of founders who carry particular diseases will be influential. Thus Afrikaners in South Africa have an elevated risk of heart disease because of influential founders who brought a genetic condition to the country in the 18th century. The relatively small breeding population led to its rapid propagation.

An important influence on inbreeding is the broader mating system. If there is extensive clan structure then multiple lines of relations start forming and reinforcing. A first cousin may be much more than just a first cousin in such a scenario, because more distant lines of relationship accumulate. Anyone who reads a textbook on population genetics will be struck by the very first assumption made, which is that the population in question mates randomly. But real human populations do not do this. It is a simplifying assumption to make the problem tractable, as all models must do. Physicists assume billiard balls are perfectly inelastic. But billiard balls really are approximately inelastic, whereas in highly structured populations, where people marry within clans, or within castes, the simplifying assumption of random mating may be very far off the truth.

Outbreeding Considerations

Does it pay genetically to deliberately outbreed, even to the extent of seeking out cross-racial mating? There is some evidence that all things being equal otherwise, there is some benefit to being deliberately outbred. This is often referred to as hybrid vigor, or heterosis. A famous study conducted in Hawaii by Nagoshi and Johnson (1986) found some support for a 4 point average IQ gain among the offspring of European-Japanese offspring. However in a large breeding population, recessive genes with clearly bad effect are pretty rare, so that far more is to be gained from avoiding close inbreeding, all else being equal, than there is from deliberate outbreeding. Which is to say, you don't have to go all that far afield.

The key qualifier is "all other things being equal". As stated above there may be tradeoffs to consider. Especially if you are a Rothschild. Or a Darwin.

Find Out How Inbred You Are

Since we are all humans and share a common ancestor, it turns out that we all have some degree of inbreeding.

To find out how inbred you are, click on over to traitwell.com/consanguinity and upload your DNA. It is free and informative.

We can directly estimate from internal examination of your DNA approximately how inbred you are. We also show you where you stand with respect to other individuals and historical examples. We don’t even need to know your family tree. It's all right there in your genes. This is actually the most accurate method for estimating inbreeding, since pedigrees usually contain errors. Check out our Consanguinity Calculator and let us know what you think.

Too bad traitwell won't respond to my complaints about their lack of results on behalf of my own consanguinity score